As I begin to talk to clients about film investing, I have discovered that the people interested in funding movies and the producers interested in making movies disagree about the level of funding necessary to proceed with a film. Investors, as you might expect, want to make the movie for as little as possible and typically quote a figure of $100k as reasonable. Experienced producers, however, insist that no project budgeted at less than $1M is worth pursuing. Who is right?

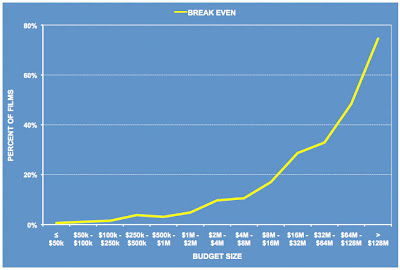

To answer this question, I sorted all of the films in my database by budget size and divided the list into various buckets from films made for less than $50k to those with budgets greater than $128M. [The database, btw, now includes 6600 titles. I only used the 5500 films with complete revenue and budget data and released between 1998 and 2007 inclusive. ROI was calculated using a proprietary formula designed to model standard industry contracts.] Next, I plotted what percent of each bucket managed to break even. As you can see in the chart below, a clear trend emerges. A higher percentage of films in the larger budget categories earned a positive return.

Chart 1: Percentage of Films That Break Even at Various Budget Levels

This result is not surprising. The studios discovered in the late 80s and early 90s that event films such as Batman and T2 generated coverage from the entertainment press. This free marketing -- or buzz -- helped drive revenues. This rationale was used to justify larger and larger budgets for tentpole films. [A tentpole film is a large, blockbuster movie that supports the studio's entire annual slate with the revenue it is expected to generate.] The phenomenon became self-reinforcing as top talent, whose gross point deals encouraged the selection of projects with the highest box office, gravitated to movies with bigger budgets, and the studios threw the financial muscle of their marketing divisions behind these blockbusters, spending enormous sums on marketing in order to protect the large upfront costs associated with producing such films.

Is the best strategy, then, to invest only in those films that cost more that $128M? The answer is no and for two reasons.

One, the established players, the studios, have a competitive advantage in this space. They are already producing big, expensive movies and doing it well. With the cost of production facilities amortized over many films and many years, the studios have achieved economies of scale that first-time entrants are not likely to match. It is necessary to find another category of film in which to compete.

Two, it requires an enormous capital investment to diversify a portfolio of big budget films. Remember that while big budget movies are less risky than low budget projects, even blockbusters fail. These failures are extraordinarily expensive. Speed Racer and The Invasion, each of which lost more than $70M after marketing costs are included, are just two examples from the past year. To protect one’s investment from the occasional failure, an investor would have to build a portfolio of films rather than invest in a single project, and to do so at this elevated budget level would require an outlay on the order of $500M to $1B.

Chart 2: Risk Profiles at Various Budget Levels

The chart above shows risk profiles for films of various budget size. This chart is similar to a topographical map, but the contour lines indicate levels of constant risk rather than constant elevation. Along any given line, the investor assumes an equal amount of risk to achieve the ROI shown for a particular budget level. For example, the risk associated with the 75th-percentile line is greater than that for the 25th-percentile line because the film must outperform 75% of all other films in a budget category rather than outperforming only 25% in order to reach the ROI indicated. Even along the high risk 95th-percentile line, films made for less than $1M do not earn a positive return. While a high level of risk is not inherently bad, you do want to be compensated for the risk that you take. Films made for less than $1M are characterized by both a high level of risk and a low rate of return. The savvy investor will shift to the right along a suitable risk contour, capturing a higher rate of return for the same level of risk.

Thank you to Kylee Heap for editing this article and for helping to clarify the concept of risk contour lines.

No comments:

Post a Comment