By Loren Sklar

Michael Lewis’s books seem to play a recurring role in my life. I first encountered his writing when I worked at Goldman Sachs on the Equity Derivatives trading floor. For those of you unfamiliar with a trading floor, it consists of a long, continuous desk crammed every four feet with two computer screens, a phone, and an angry trader. Over six hundred phone lines can ring at any time, and if any one of the lines isn’t answered before the third ring, one of the head traders will scream, “Pick up the f***ing lights!” The phone lines are called lights because, in addition to ringing, a light will flash on the console indicating which line it is.

In my first month on the trading floor, I dreaded picking up the lights, not because I couldn’t help the customer on the other end of the line, which I couldn’t. I feared answering the phone because all of Wall Street is on a first name basis, and I didn’t know which Andy, Mike, or Tom the person wanted to talk to. I was scared of the phone, but I was more scared of disappointing my bosses so, after two rings, I would cautiously hit the blinking light and say, ”Hello, Goldman Sachs.”

Some time during that first month, I picked up the phone to hear a voice asking to speak to Dave. Luckily, only one Dave worked in Equity Derivatives so, brimming with confidence, I called over to David Rogers, one of the partners, and asked if he would take a call from a John Meriwether. I heard several chuckles from the people around me. I asked my deskmates what was so funny, but no one would explain the joke. The next day, a copy of Lewis’s

Liar's Poker, in which John Meriwether plays a prominent role, appeared on my desk. Meriwether had been calling to discuss the final details of unwinding Long Term Capital Management’s $3.6B bailout, an obviously important phone call that no one clued in to the goings on of the trading floor would want to screen.

Another of Lewis’s books,

Moneyball, helped inspire my current analytical curiosity regarding film financing. The book focuses on the general manager of the Oakland Athletics, Billy Beane, and his statistical analyst and sabermetrics guru, Paul DePodesta. The Oakland As are a small market team and, due to limited financial resources, are forced to use statistical information to identify and hire undervalued players. Beane asks the questions, “How do you evaluate an individual’s contribution to a group effort? How do you value talent? And can incorrect assumptions about the value of talent be exploited to overcome financial disadvantage?” By using information better than anyone else, Beane is able to assemble a perennially competitive baseball team at a small fraction of the price.

My area of expertise is film, and I started to ask the same questions about film production. Is an above-the-line star primarily responsible for box office results, as is commonly assumed, or do other of a film’s collaborators contribute just as much to a film’s financial success. If so, which ones? What metrics are used to price talent, acting and otherwise? Is it possible to develop a more insightful set of statistics? And, most important, can an under-funded independent film producer exploit a deeper understanding of statistics to compete with $100M Hollywood tentpoles?

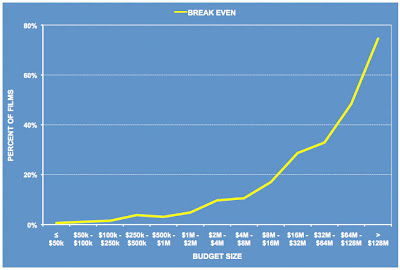

In baseball, a player who is able to maintain a .300 batting average is considered successful. In Hollywood, only three in ten films must break even in order for the slate to be profitable overall. Lewis's

Moneyball shows us that a baseball manager can employ statistical analysis to assist in picking those players capable of achieving this benchmark. My goal is to demonstrate how a similar approach might prove fruitful in selecting which film projects to finance.

Source for box office data: Variety

Source for box office data: Variety